Table of contents

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History

We apologise for the laws and policies of successive parliaments and governments that have inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on our fellow Australians. We apologise especially for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country.

– Kevin Rudd

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were among my closest friends from an early age. There was a strong connection. However, during my adventurous years growing up in Edmonton, I was unaware of the rich history of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander struggle for justice, right here in Gimuy.

Assimilation of First Peoples

Children taken from their parents (the Stolen Generations) were taught to reject their Indigenous heritage and forced to adopt white culture. Often their names were changed. In addition they were forbidden to speak their traditional languages. Some children were adopted by white families, and others were placed in institutions where abuse and neglect were commonplace.

Legislation and policies excluded Indigenous people from participation as equal citizens. This saw the removal of many Indigenous people from their homes to missions and cattle stations. Consequently, their lives were lived under regimes of surveillance and control, with a distinct lack of personal liberty.

Just as Aboriginal people had resisted invasion during the frontier wars, there was also a strong and concerted resistance during the 1950s and 60s. It was non-violent, but very passionate in nature.

The resistance came not through electoral politics, but through Aboriginal people themselves taking leadership and fighting for change. One area of resistance where Aboriginal leaders took on strong leadership roles was the trade union movement.

Joe McGinness: Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Champion

Born in 1914, around 50 kilometres south of Darwin, Joe McGinness was the youngest of five children born to Irish immigrant, Stephen McGinness and his wife Alyandabu, a Kungarakan woman also known as Lucy.

McGinness worked as a truck driver in the 20s and 30s, and joined the army after the bombing of Darwin. He served with the field ambulance in Darwin, Morotai and Borneo.

During the 1930s Joe became known throughout North Queensland as a fighter for the rights of Australia’s First People.[1] However, it was after the war that ‘Uncle Joe’, as he became known, focused on this struggle. Most notably he took on the ‘protection laws’ that gave state governments almost total control over the movement of Aboriginal people.

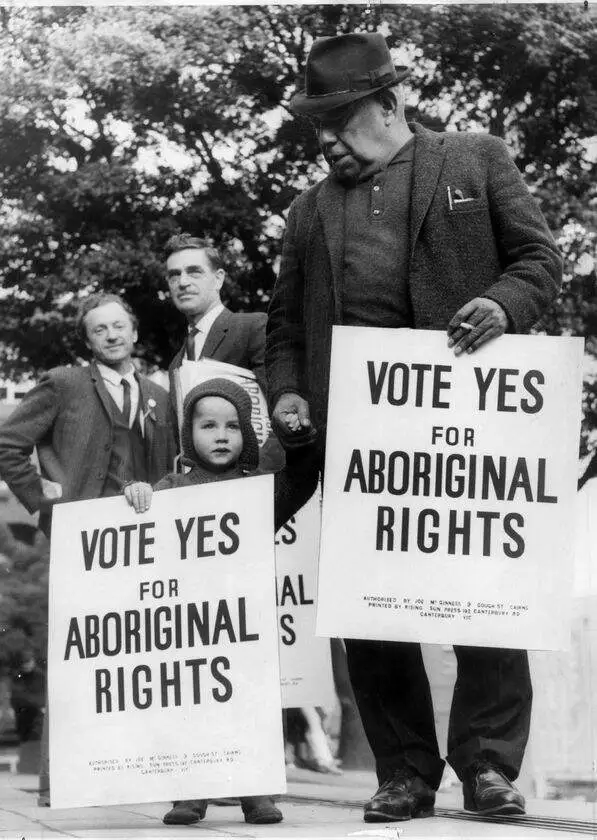

In response to these racist laws, Joe dedicated much of his time to campaigning for the 1967 amendment to the Australian Constitution. Above all, this amendment granted constitutional power to the Federal Government to legislate in favour of Aboriginal people. Further, it allowed Indigenous Australians to be counted in the census.

Joe moves to Cairns and joins the Union

McGinness moved to Cairns in 1951, where he met his second partner, Amy Nagas. He helped care for Amy’s two sons, Raymond and Samuel, and their daughter, Sandra, who was born in 1954. [2]

Like most regional towns of that era, Cairns had distinct racial divides. Most Aboriginal people lived on the outskirts of town, surviving on intermittent, underpaid work. However, McGinness was determined to fight the discrimination and abuse directed at the local Indigenous community, largely by employers and police.

After joining the Waterside Workers’ Federation while working on the wharves on Thursday Island, McGinness expanded his activism. In Cairns his involvement with the union grew, culminating in his election to its executive committee.

In 1958 The Cairns Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Advancement League was formed with McGinness as its secretary. The league worked closely with the local Trades and Labour Council which McGinness described as ‘the only white organisation that showed concern over reported cases of injustice’.[3]

Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

Increased activism by the Cairns League coincided with an emerging national movement in support of Indigenous rights. Indeed, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, commonly known as FCAATSI, was formed after a coalition of rights groups met in Adelaide in 1958. McGinness became FCAATSI’s first Indigenous President. He held the position for 17 years between 1961 to 1973 and 1975 to 1979.

Before long FCAATSI won its first victory of national significance. A young Indigenous man at the Hope Vale Mission who had consorted with his girlfriend, was flogged by the mission’s pastor and ordered to be moved to Palm Island. McGinness campaigned long and hard against the pastor’s actions.

McGinness and his comrades forced the government to hold an inquiry into the incident. It found that the pastor’s behaviour was ‘inexcusable’. It was the first time this type of misconduct by a mission had been successfully challenged. The win triggered a range of protests against similar incidences of abuse across the country.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders: 1967 Referendum

The Hope Vale case was McGinness’ first major victory, and there would be many more. FCAATSI pursued important law reform, including wage equality cases and the early push for land rights. However, McGinness is best remembered for his role as joint national campaign director during the lead-up to the 1967 referendum.

Driving from town hall meeting to town hall meeting, he was part of a grassroots campaign across the nation.[4] The referendum was FCAATSI’s strongest and most successful campaign. Supported by more than 90% of voters, it remains the strongest ‘yes’ vote of any Australian referendum.

McGinness Remembered as Champion of First People

In North Queensland, Joe McGinness became the regional manager of Aboriginal Hostels in Cairns, and was instrumental in the establishment of many of the major Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations.[5] He became a key figure in the early days of the development of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs. Patrick Dodson later wrote of Uncle Joe:

“This grand old man has been the inspiration to many of us who have joined in the battle for justice. He has provided wisdom and advice, guidance and correction, humour and hope. His interest, enthusiasm and point of view on the continuing challenges we face against the ignorant and arrogant who professed to know what is best for us. He was always present and available as he encouraged us on.”

Gladys O’Shane: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Rights Advocate

Born in Mossman, Far North Queensland in 1919, Gladys Davis obtained her first job working at the Mossman Hospital Laundry. There she met Irish immigrant Patrick O’Shane and they fell in love. The pair were married in October 1940.

Gladys and Patrick moved to Cairns where Patrick became known as ‘Tiger’ O’Shane. A moniker he earned for his fighting ability when taunted for his marriage to an Aboriginal woman.

Tiger worked as a wharfie on the Cairns Waterfront, joined the union, and became politically active. Gladys commenced her political life during the 1954 national Waterside Workers’ strike, supporting Cairns wharfies during the dispute. Four years later she showed her passion for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, addressing the Waterside Workers’ Federation Women’s Committee national conference in Sydney.

Gladys O’Shane: Champion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and a Communist

Gladys O’Shane informed the audience that the Queensland Aboriginals Preservation and Protection Act was ‘as vicious as any Crimes Act’ and that it was the Director of Native Welfare – not the parents – who was the legal guardian of every Aboriginal child in the state. Therefore, she urged the women to ‘join with us in our struggle for a better way of life’.[6]

Gladys was elected as the inaugural president of the Cairns Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Advancement League in 1960. The Cairns league took on cases involving abuse of Aboriginal people.

An alliance of the Cairns Trades & Labour Council and the Cairns League succeeded in publicising these cases, often bringing the offenders to justice. O’Shane had a wider influence through the Cairns League’s affiliation with the national body, the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement.

O’Shane joined the Communist Party (CPA) in 1960. She attended Party summer schools where she developed her public speaking skills. In 1964 she was elected to the North Queensland District Committee of the CPA.[7] When she died of a heart attack in 1965, Gladys O’Shane was mourned as a champion of our First People.

Communist Fred Paterson

Born in 1897, Fred Paterson was politicised by the First World War. Fred saw workers on each side of the front line massacring each other for no reason, at the behest of a wealthy ruling class.

A prize-winning student, Paterson was awarded a Rhodes scholarship to study at Oxford and could easily have become a wealthy barrister. However, Fred’s only goal in life was to improve the lives of working people and advance the cause of socialism.

Paterson explained in his memoir that, for him, practising law was always a part-time pursuit. Most of his time was spent working for the Party: “Between cases I did an enormous amount of work for the Communist Party, addressing meetings all over North Queensland, from the coast to the Northern Territory border.” Two of Fred’s many clients were Joe McGinness and Tiger O’Shane. Fred was a strong ally of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Fighting Racism and Fascism

Fred Paterson’s work in the fight against fascism and in defending unemployed migrants forged his reputation. During the Great Depression, Queensland had the highest number of Italian immigrants of any state.

New arrivals, having escaped Mussolini’s fascist regime, often moved north from Brisbane looking for work. Consequently, Australia’s first anti-fascist march was held in the Far North Queensland town of Halifax in 1925. While the government cracked down on these radical protestors, Fred stood in solidarity with them.

AWU ‘sells out’ as CPA ‘stands up’

Anti-migrant racism resurfaced in 1931 when cane farmers and the conservative Australian Workers Union (AWU) made a deal to give British subjects farm work ahead of Italians. Paterson contested the legality of the deal. In 1933 a deadly epidemic of Weil’s disease broke out in the sugar cane farms and the cutters went on strike.

By August 1935, 2000 workers had shut down the sugar mills. When the state government refused relief to laid-off workers, the CPA in the unions organised fundraising, communal kitchens and accommodation. Although the strike had only limited success, it raised the profile of the CPA and fuelled resentment towards the Australian Labor Party (ALP). Paterson’s support for the cane cutters helped him win election to the Townsville local council in 1939.

Working with allies from a ‘left wing split’ within the ALP, Paterson had enough influence on the council to make real improvements for local people. This including providing cheap stoves for Townsville workers, as well as establishing public libraries, a swimming pool and a public ice works (when the military took over the existing one during the war).

Fred fought for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

Fred represented Jacko, the victim in the Hopevale flogging case, free of charge. His friendship with Joe McGinness and Glady’s O’Shane saw him engage in considerable free advocacy on behalf of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indeed the Communist Party was the first political organisation to champion the cause of Australia’s First People.

From its foundation in 1920, the CPA and its members were uncompromising opponents of racism against Australia’s Indigenous people.

The CPA criticised ALP policy on Aborigines. The July 1, 1927, issue of Workers’ Weekly rejected the near universal view propounded by bourgeois historians and politicians that Australia had been settled without violence against, and resistance from Aboriginal people.

The Weekly called out the facts, informing readers that from the outset the colonisation of Australia was accompanied by the attempted “physical extermination” of the Indigenous people, and that “inhuman exploitation, forced labour and the “slavery” of Aboriginal workers continued, especially in outback pastoral industries.

Fighting ‘The Ban’ and Winning Bowen

The Communist Party was banned in 1940 and consequently it became an offence for Patterson to publicly address a crowd. During a visit to Cairns at this time, Patterson used his legal experience and creativity to work around this problem. He addressed a meeting of locals while standing on a table, metres off the Cairns Esplanade. He knew the local constabulary could not enforce the Communist ban on him, because he was beyond the high-water mark, so outside their territorial jurisdiction.

In the campaign for the seat of Bowen in the 1944 state election, Paterson defeated the ALP incumbent Dick Riordan. Paterson declared in one of his first speeches to parliament in 1944, “Socialism is in accordance with the highest and noblest traditions and ideals of mankind. But socialism cannot be imposed upon the people by a minority. It is a movement in the interests of the vast majority and will come into existence only when a majority of the people want it and are organised sufficiently to obtain and maintain it”.

Paterson Attacked

The biggest test for Paterson came in 1947 and 1948 with the Queensland rail strike. Rail unions applied for a flow-on of a pay rise won by metal workers under federal awards. The ALP Hanlon government – despite Hanlon being a former railway worker himself – refused their claims. Workers took strike action in response.

Determined to defeat the strike, the State Government launched a propaganda campaign against the rail workers. Indeed they accused them of being taken in by a Communist plot.

In support of the railway workers, Paterson took shifts on the picket line every morning, offering the strikers legal advice and using Parliament to publicly defend the strikers. On St Patrick’s Day 1948, while taking part in a rally of railway workers, Paterson was attacked by a plain clothes policeman. His skull was bashed in with a police baton. His injuries were so severe that he was not expected to survive.

ALP and capitalist press join forces

The day after the bashing, the Courier Mail quoted the ALP Premier expressing indignation at the demonstrators’ behaviour and admiration for the police. Hence, the article called the events “a deliberately provoked brawl by the communist element which saw defeat staring it in the face. I have reports of their [police] tolerance, patience and care in handling people during this difficult period”.

This police violence marked the end of Paterson’s political career. He struggled to recover from his injuries. The ALP government also redrew the boundaries of his electorate, making it un-winnable for him.

Paterson’s story of struggle and resistance guarantees his place as the only Communist ever elected to Parliament in Australia.

First People and Good Memories

Much injustice took place in the post war decades, most notably the appalling treatment of our First Peoples. This included the theft of land and the tragic removal of children. However, oppressed people themselves, with inspired leadership and good allies never gave up. They fought for change.

Whether it was McGinness and O’Shane fighting for the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, or Fred Patterson fighting for the rights of people starving during the depression, class struggle had been the precursor to better days.

All Chapters:

- Far North Queensland

- Growing up in Australia

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Queensland Political Culture

- Princess Alexandra Hospital Spinal Unit

- People with Disabilities

- Cairns Regional Council

- Conservative Cairns Council

- ALP Qld

- Abortion Law Reform

- Fighting Fossil Fuel

- Local Government Corruption

- Losing to Labor

- My Cairns Council Return

- Council Mayors Silencing Dissent

- Socialist Alliance and Fighting Fascism

- Jenny Pyne, Life and Pain

- Cairns Council Members Lurch Right

- Fightback and Farewell

Struggle and Resistance in the Far North

Notes and Pic

[1] Newsletter of the Federal Council for Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, January, 1967.

[2] Heroes in The Struggle for Justice. http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/heroes/biogs/joe_mcguinness.html

[3] As Above.

[4] Heroes in The Struggle for Justice. http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/heroes/biogs/joe_mcguinness.html

[5] As Above.

[6] Maritime Worker, 11 November 1958