Far North Queensland has “been constructed as the site of the Other, of that which has been repressed in the south’s production of the real.”

Jon Stratton

Table of contents

Far North Queensland

Prior to the revolution in technology and communications and the introduction of affordable air travel, Far North Queensland was a long way from anywhere. It was isolated and remote as far as most of the modern world was concerned. However, it had a very distinct environment and culture. It was in the Far North Qld town of Gordonvale that life began for me on the 23rd of April 1967.

Situated about 23 kilometres south of Cairns, Gordonvale was a small country town of about 2000 people. Established on Yidinji tribal land, it was initially called Mulgrave and later renamed Nelson. Gordonvale was finally settled on as a tribute to John Gordon. A pioneer in the district, he was a butcher, dairyman, grazier and early director of Mulgrave Sugar Mill.

The town’s most prominent geographical feature is a cone-shaped peak resembling a small volcano, known as Walsh’s Pyramid or Djarragun. Surrounded by cane fields on the outskirts of the town, rising 922m, it is a sight to see.

Doc Davis

In 1967 Gordonvale had a sugar mill, four hotels, a tennis club and a police station. It also had two GPs, Dr Janus Brodie and Dr Raymond Davis.

Most importantly, on the day of my birth, Gordonvale had the nearest hospital to Edmonton. On the 23rd of April 1967, Tom Pyne and his pregnant wife Marion, both keen tennis players, were at Norman Park, Gordonvale watching tennis.

As luck would have it, another keen participant in the tennis was Dr. Raymond Davis. Not long into the day, labour pains led to my parents and the man referred to simply as ‘Doc’ making a 400-metre trip down Norman Street to the Gordonvale Hospital.

Born as a result of a ‘love match’, I had none the less ruined Doc’s day of tennis.

Dr. Raymond James Davis (1926-2012) – An FNQ Bio

Raymond James Davis (known to many simply as ‘Doc’) was the son of an English policeman, Willian Davis and his wife Germaine. Doc was born in Alexandria, Egypt, where his father was stationed. The family returned to England to live in Swindon, where the young Raymond excelled at school and received a scholarship to study at Kings College, London.

‘Doc’ married his wife Jill in 1949. Unfortunately, he contracted Tuberculosis post WW2. He had one lung removed and spent long periods in rehab. Later he took the adventurous step of applying for a job in the Government Gazette as the Superintendent of Yarrabah hospital in Far North Queensland.

Doc flew to Australia in 1956. Jill later followed with their their three children, Jon, Yvonne and Harry, arriving in Sydney in 1957. Doc travelled south to collect them, returning from Sydney to Gordonvale in an old battered Morris, camping beside the roadside at night. In Gordonvale he took up the Medical Superintendents job at Gordonvale Hospital.

Doc Davis died in 2012, his wife Jill having died a few years earlier. While Doc’s contribution as a medical practitioner was immense. I remember him for his humanity. For example, seeing itinerant people, often Aboriginal, asleep in public areas was sadly not unusual. It was routine enough that most people would simply walk past a motionless body on the footpath assuming intoxication or simply not caring at all. Not Doc, he would stop, and check for breathing and wellbeing. For him the ‘Hippocratic Oath’ was not a formality, it was his life.

Edmonton

North of Gordonvale was the town of Edmonton, halfway between Gordonvale and Cairns. Edmonton had a smaller population than Gordonvale, and a much smaller population than Cairns, which had a bustling 54,000 people. Edmonton also had a sugar mill and was typical of most country towns of that time.

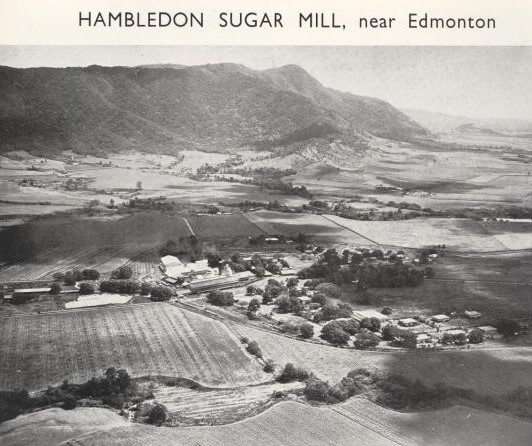

The town had two pubs, the Hambledon Hotel and the Grafton Hotel. The main sources of employment were a meat-works on the outskirts of town and the Hambledon Sugar Mill. There was also a strong sense of community, which was characteristic of most country towns.

My Home in the Far North Queensland

I was the second child of Tom and Marion, my sister Joann having been born 7 years earlier. We shared a small red brick house at 88 Mount Peter Road.

Formerly known as Sawmill Pocket Road, Mt Peter Road was (and remains) the longest road in Edmonton. It starts at its junction with Mill Road near the Bruce Highway, running for a mile before getting to what was our home. It then curled its way through sugar-cane paddocks, ending at a small goldmine in Mount Peter, in the hills behind the township.

The house at no. 88 was surrounded by a creek to the north and east and cane paddocks to the south. To the west of our house lived my mother’s parents, Bob O’Connell and May McKinnon, known to my sister and I simply as Grandad Bob and Nana.

Marion married Tom in 1955 when she was eighteen and he was twenty. Tom and Marion Pyne joined two pioneering families of the Far North, the Wienerts and the Pynes.

Far North Queensland Weather

The tropical weather in Far North Queensland can be characterised as wet, hot and humid. While four seasons common in most of the world in the tropics there are just two seasons, the ‘wet season’ and the ‘dry season’.

The wet season (December to March) is characterised by frequent and intense rain showers, thunderstorms, and sometimes tropical cyclones or hurricanes.

While high humidity makes life ‘sticky and uncomfortable’ the warm humid weather has resulted in the formation of unique tropical rainforests and lush vegetation.

When I was growing up, summer included many family visits to the Mulgrave River to cool down. At 88 Mount Peter Road we did not have air-conditioning until I reached 12 years of age. It was a delight!

The dry season has reduced rainfall and is marked by clear skies and a welcomed drop in humidity levels. In addition, while daytime temperatures during ‘the wet’ range from 25°C to 35°C (77°F to 95°F), they drop a few degrees during the ‘dry season’.

Putting Down Roots in Far North Queensland

The Far North Queensland I had come to know and love was special. Edmonton had for thousands of years been home of the Yidinji people. Their traditional ways and movements stretched back longer than anyone knew. When the European invasion came, what kind of people moved here and why?

Drivers for European people to leave their homeland were varied. They included economic hardship, political persecution and a love of adventure. Consequently, for many Far North Queensland was an environment full of new opportunities.

James Pyne: A Pioneer of the Far North

The Pyne name has been in Cairns since the early days of settlement. My great-great grandfather, James Pyne arrived in Brisbane in 1865 with his wife Emily and their three children. They had sailed from Gravesend, Kent in England aboard the ‘Empress of the Seas’.

Far North Queensland Towns

It was not long before James determined to head further north. Skippering the schooner “The Freddy” he sailed the east coast waters, taking supplies to the fledgling Far Northern settlements at Port Douglas and later Cairns.

A pioneer of the Far North, he went on to become one of the founding fathers of Cairns. Merchant, landowner and philanthropic businessman, James Pyne became an original member of the Cairns Divisional Board. It was the Council of the day, at a time when Cairns was carved out of mosquito-inhabited mangroves.

The Queensland government showed support for the area when they passed the Divisional Boards Act in 1879. Consequently the Government included the Cairns district under the Division of Hinchinbrook (centred on Ingham).

The Government appointed Louis Severin and James Pyne as the Cairns representatives on the Divisional Board. However they both complained about the difficulties of travelling to Port Douglas. As a result, the Johnstone Divisional Board was proclaimed. Further amendments saw Cairns Division begin at Double Island, head west to where Mareeba now is, and south to just north of the Johnstone River.

Roads and the Far North’s First School

The first six Cairns Divisional Board representatives were elected in 1880. They held their first meeting on the 20th of July that year at the Cairns Court House. The Board’s primary focus was building roads.

Cairns’ first school was located on the Esplanade, before moving to the block bounded by Lake, Aplin, Abbott and Florence Streets. James Pyne donated this land to the Secretary for Public Instruction (now the Education Department) in 1878.

The school closed at the end of 1994 and the State Government sold the block in July 1995. Today an overseas-owned resort hotel occupies the site. While today this land would be worth many millions, it held little value in 1878.

Babinda

James Pyne’s position as a businessman and landholder were not to be characteristics of his descendants. His great grandson, my father Tom, was born in 1935 in one of Australia’s most beautiful and wettest areas, the Far North Queensland town of Babinda. A lack of material wealth was compensated for by the natural beauty of the environment Tom grew up in.

Babinda, nestled at the base of Mt Bartle Frere, Queensland’s highest peak, was 40 minutes south of Gordonvale. Tom went to Bellenden Ker State School about nine miles north of Babinda. His father Jack owned a small cane farm at a place called Deeral.

Jack (Christened John) and his wife Katherine were salt of the earth people. They had 5 children, the oldest of the brood being Jack, followed by Ethel, Frank, Grace, and then Tom the youngest.

Frank and Cheako

Frank joined the allied armed forces occupying Japan. While in Japan he met and fell in love with a woman named Cheako. Such an occurrence was not unknown. Indeed, with so many young men marrying, the term ‘Japanese War Bride’ was born. However, back in Australia anti-Japanese sentiment remained strong.

The hostility was raw. In some ways it was understandable, following the inhumane treatment of Australian troops during the war. So, when Kate Pyne went to the train station to welcome her son home and embraced his new Japanese wife, there was every reason to believe her heart was breaking. That hug would not have been just for the benefit of Frank and family members. It was also to send a message to any other onlookers that this woman is “one of us”.

The racism that was such an entrenched part of Far North Queensland ensured Frank focused inwards on his family. He ensured they were protected and loved. Working at the Mulgrave Mill he focused on home and family and avoided the anti-Japanese sentiment of the time.

Wienerts Arrive in Far North Queensland

On my mother’s line, Johan Wienert was born on a boat making its way to Australia from Germany in 1881. He was born to parents Peter and Anjie Wienert. After arriving in Australia, the family settled in Cooktown. In true Aussie fashion, young Johan became Jack.

Jack married another European arrival to Far North Queensland, Johannah Thygesen from Denmark. They built a home in Edmonton and one of their children was my grandmother, Christina Margaret May Wienert. Born in Gordonvale on May Day (1st May) 1915, Christina Margaret May Wienert was from that day forth known simply as “May”.

May married a Scottish man named McKinnon at the tender age of 18. McKinnon was a wanderer and abandoned May with child (Isobel) disappearing to parts unknown. Young May soon met my grandfather Robert (Bob) O’Connell. They fell in love and had a child (Marion) together.

Bob had been born into a Catholic family living in Kenny Street in 1912. He and May met during the depression and had not been together long when war with the Japanese broke out. Bob resigned from his exempted job as a bridge builder. He joined the army and was captured in the fall of Singapore. He spent the remainder of the war in Changi prisoner-of-war camp.

Bob and May

Bob O’Connell’s generation could well be described as ‘the great generation’ for their contribution to our nation. They gave their all in the war, fighting fascism. This was at a time when, for Far North Queensland, the threat of invasion was real and the enemy close.

Like many other survivors from Changi, Bob returned home from the war starved and emaciated. You could count every rib on him. Bob also carried a scar halfway between his shoulder and neck, the result of not displaying the required respect to a Japanese soldier. The poor state of Bob and other survivors improved over time.

While the physical scars disappeared, far more problematic were the emotional scars. Back then the term ‘Post Traumatic Stress Disorder’ had not yet been invented. Even if it had, I doubt the men of that era would have readily embraced it.

The Hambo

The only thing that passed as medication for Bob O’Connell were his two daily trips to the Hambledon Hotel (the Hambo): his morning session and his afternoon session.

At the Hambo, Bob O’Connell gave new meaning to the term “regular”. You could set your watch by his arrival and departure during the morning and afternoon sessions.

Fortunately, except for a few metres, it was a straight line from his home at 90 Mount Peter Road to the Hambo. Drink driving was not the concern back then it became later. His old Toyota Corolla knew the journey that well that it would have driven itself to the pub and back whether Bob was at the wheel or not.

Bob had left his Catholic wife who would never divorce him and May never heard from the degenerate McKinnon again. And so it was that my mother Marion was born out of wedlock in 1937.

The Good Life in Far North Queensland

I cannot imagine a more carefree or relaxed lifestyle than growing up in Edmonton in the 1970s. Surrounded by cane fields and with close access to tracks, trails, creeks and swimming holes, it was heaven.

The small population ensured serenity as I adventured through the landscape. The peacefulness was interrupted only occasionally by the cane trains during harvest time. The harvest period was known as the ‘crushing season’. Locomotives were loaded to take the sugar cane to the mill to be crushed.

Life was relaxed, and living was easy. In 1971, when the leader of the Liberal Party, Malcolm Fraser uttered his famous words, “life was not meant to be easy”, it was hard to believe him. Certainly Cairns was a very egalitarian town with its own raw energy.

Far North Queensland Map

Far North Queensland (FNQ) is the northernmost part of Queensland. In the south Far North Queensland starts at Cardwell Division on the Cassowary Coast Council. FNQ also stretches north to include all of the Torres Strait, and west to include the Gulf Country.

There were massacres of Aboriginal people in the region. A number of these massacres have been documented by Dr. Timothy Bottoms in his landmark work Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland’s Frontier Killing Times published in 2013.

Oppression of the Traditional Owners in Far North Queensland

Early European arrivals to Far North Queensland had no understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people or their place on country. Inhabitants of the area for thousands of years, our nation’s first people were more than occupiers of the land. They were part of the landscape in a way that the new arrivals could never comprehend. Their movements across the region gave them access to the natural bounty they needed to maintain health and nutrition, and the land they needed to maintain their stories and ancient cultural practices.

In Edmonton, the Aboriginal inhabitants, later to be recognised as the traditional owners, were the Yidinji people. As with all Aboriginal people, their relationship with the land had evolved over thousands of years. They considered themselves part of the land and the land to be part of them. This connection was not just practical, it was deeply spiritual.

Polite white society established the myth that the traditional owners had not fought to protect their land and were not massacred. None of this was true. Frontier wars took place across the nation as indigenous Australians fought for their country. They fought and died in countless battles to protect their homelands.

Skeleton Creek: A Far North Queensland Massacre

Growing up, I never knew how Skeleton Creek north of Edmonton gained its name. I later learned it had been the location of the massacre of a number of Aboriginal men. Their heads were cut off and left on stakes for all to see, to send the message not to fight back. That is how this trickle of a waterway obtained its name.

Some of the skulls of those murdered were eventually sent back to England to be ‘studied’ so Europeans could gather a better understanding of these beings from Australia. We would later see them returned to country and put to rest. There were no treaties made with the traditional owners at this time; in fact, they were barely seen as human.

The mistreatment, abuse and murder of many traditional owners remains a dark stain on Australia’s history and this was no different in the Far North. The ‘frontier mentality’ of the settlers remained long after other regions had established a more peaceful mindset.

By the turn of the century Australian Governments had resolved to take ‘responsibility’ for Aboriginals. By 1911, every mainland State and Territory had introduced ‘protection laws’. These laws subjected Aboriginal people to near-total control. They did not have freedom of movement, labour, custody of their children or control over personal property.

Mission Life

The “Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act (Qld) 1897” allowed the Chief Protector to remove local Aboriginal people and relocate them onto missions. As a result, ‘missions’ were created by churches or religious individuals to house Aboriginal people and indoctrinate them in Christian ideals. Indeed many aspects of South Africa’s Apartheid system were modelled closely on Queensland’s Aboriginal Protection Act.

The closest mission to Edmonton and Gordonvale was that of Yarrabah. Yarrabah was established on the traditional lands of the Gunggandji people at Mission Bay on the Cape Grafton Peninsula, just south of Cairns.

The Director of Native Welfare was deemed the legal guardian of all ‘aboriginal’ children, whether their parents were living or not. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were taken from their families. Subsequently these children became known as the Stolen Generations.

By the time of my childhood, these apartheid controls had been removed. While I recall no racism in the playground of Hambledon State School, as an adult there was no avoiding it. Considering our history, it should surprise no one that racism remains commonplace in much of Far North Queensland today.

A Sweet Start in Far North Queensland

If there was no way of sugar-coating the treatment of the traditional owners, the establishment of white settlements was certainly coated in sugar. The sugar industry was not something I thought about a lot growing up, yet it was omnipresent. The sugar industry influenced everything from our economy to the landscape to many of the personal friendships formed.

Cane Fires

By the 1970s the industry was transitioning to green harvesting, but cane fires were still commonplace. This was helpful for harvesters, particularly where fields had large rocks or other hazards that may otherwise have been hidden by the weeds and other vegetation.

Cane cutting by hand no longer occurred when I was growing up. However old cane knives could still be found in most sheds. I can well remember making a mess of the vegetation along our creek with Grandad Bob’s cane knife. It easily sliced through any green vegetation, slashing a trail as I imagined myself a colonial explorer in darkest Africa.

During cane fires, small embers of ash around ten centimetres long and roughly a centimetre thick would float from the cane fields, blowing whichever way the wind sent them. Usually this was towards the nearest houses, to the distress of the women folk of the town who had to clean up after the ash floated through their windows and settled on newly swept floors.

One of my first childhood memories was of running in our yard, trying to catch as many pieces of ash as I could, before they hit the ground, only to have them dissolve in my palm. I would later return home with hands more black than white.

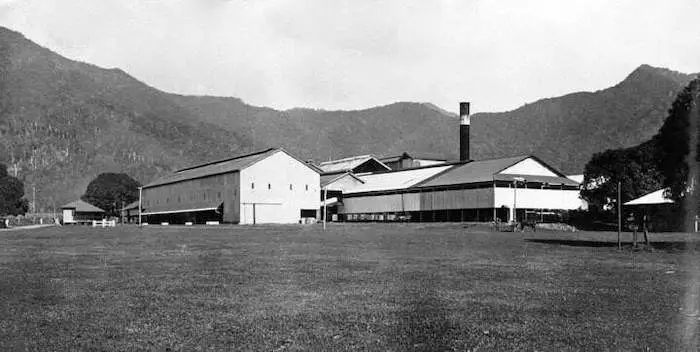

Hambledon Mill

In Edmonton the hub of industry was the Hambledon Sugar Mill, lying to the west of the township. Located next to the mill were houses for mill staff, all owned and paid for by the mighty Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR).

This mill community, while owned by CSR, was what the staff made of it. CSR employees built their own swimming pool and tennis courts to enhance the area. ‘Mill houses’ were overwhelmingly occupied by white-collar staff such as accountants, chemists and managers. There was also a single mens barracks for mill workers.

My parents formed close bonds with several members of the CSR community, to the extent that my school vacations often consisted of travelling down the Queensland coast to catch up with former Hambledon Mill employees who had moved to other coastal towns to work for CSR. These friends included people like Allan and Carol Hughes, who moved to Ingham; Don and Vai Hamilton, who moved to Mackay; and David and Jill Sanders, who moved to Brisbane.

Memories

One of my early memories as a small child was working on the ‘mill float’ for our local parade called ‘Fun in The Sun’. The float consisted of not much more than a flatbed truck with sugar cane woven into circles and decorative patterns.

Returning to this area today, one finds a water slide theme park known as Sugar World. It is hard to recognise much at all from my bygone youth. Memories are not the most reliable of tools at the best of times.

My lack of familiarity with some of the landscape today tells me that my experience of growing up was as much a product of a time in history as of geographical location. Politics during any period is likewise a product of the actors of the day and the sentiment of the time. Once gone it is all but impossible to recreate.

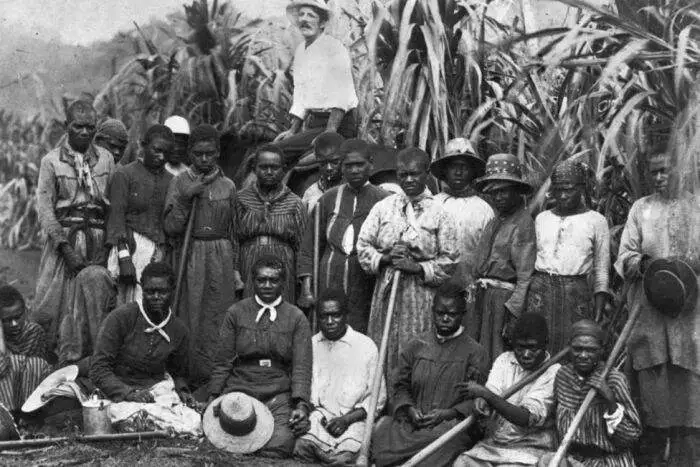

Slavery in Far North Queensland

The broadcaster Phillip Adams likened Queensland political culture to that of the deep south of the United States. Social conservatism, agrarian socialism and a strong element of racism were all part of this political culture. A tragic practice the two regions had in common was slavery.

The demand for labour in Queensland resulted in what was called ‘blackbirding’. This term described enslaving islanders to work on the sugar plantations. Over a period of 40 years, 60,000 sugar slaves were taken from Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, PNG, New Caledonia and Niue.

Ships arrive at Far North Queensland Ports

The Queensland government wanted to ‘regulate’ the trade in human beings. As a result, it required every ship engaged in recruiting labourers from the Pacific Islands carry ‘observers’ to ensure that labourers were willingly recruited. However these observers were often corrupted. Once paid off with money or grog, observers did little or nothing to protect the islanders from abuse.

The expansion of sugar plantations in Australia created market destinations for slave traders. Consequently, sea-captains continued tricking islanders into boarding their ships and kidnapping them with violence.

So many ships entered the blackbirding trade that the British Navy sent ships into the Pacific to suppress the trade. By 1808 both Great Britain and the United States had prohibited the African slave trade. However, the British ships were not able to suppress the blackbirding trade.

South Sea Islanders arrived at several major ports along the eastern coastline including Brisbane, Maryborough, Bundaberg, Rockhampton, Mackay, Bowen, Townsville, Innisfail and Cairns. Shipowner Robert Towns (c. 1794 – 1873) was the first Australian to transport South Sea Islanders for Queensland labour. They named Townsville after him.

The Don Juan

The 67 aboard the Don Juan were the first of the estimated 60,000 South Sea Islanders transported to Australia. They arrived on 807 voyages to work on Queensland sugar farms between 1863 and 1904. Thirty per cent of those brought to Australia died because they lacked immunity to many of the diseases common to the European community.

The inhumane trade in Pacific labour drew criticism from many sectors. But it was the White Australia Policy and the desire to protect the jobs of white Australians that finally ended the trade.

Repatriation and Remembering

In 1901 the slave industry ceased, and the Australian government took steps to deport South Sea Islanders back to their home islands. This was often not possible, because people’s origin had not been accurately recorded. Tragically, ship masters were overly keen to offload south sea islanders at the first opportunity, even if it was not to their original homeland. This resulted in hardship, discrimination and sometimes death for those who had helped to build Australia’s sugar industry.

The Far North becomes the Red North

The stretch of Queensland from Mackay to Cairns was in the 1930s and 40s known as “The Red North”. During this time the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) was the driving force behind the Unemployed Workers’ Union. This union provided assistance that helped many ordinary people to survive the Great Depression.

The CPA gained wider support when communist trade union leaders ran strong campaigns which won increased pay and improved conditions for workers in the mines and the cane fields.

In 1933 a deadly epidemic of Weil’s disease broke out in the sugar cane farms. Cane cutters and their families lived in constant fear of the disease. Burning the cane before harvesting was the best way to control outbreaks, but it also reduced the sugar yield, thus reducing the profits of cane growers. Growers campaigned against burning crops, shamefully winning support from both the ALP state government and the Australian Workers Union (AWU).

Communists Strike

Despite the forces stacked against them, the cane cutters went on strike. By August 1935, 2000 workers had shut down the sugar mills.

The strike was defeated by July 1936. Striking workers were evicted from their quarters and scab labour employed. The battle was lost. However, the war was won when an order for burning cane before harvesting was later handed down by the industrial court.

By the late 1930s the CPA had earned wide support and North Queensland was the biggest “red” area outside the Sydney district. North Queensland Communists interspersed their political activities with community activities. These included hospital visits, exhibitions of horticulture and handicraft, and arranging social functions.

Events including dances, balls, card parties, picnics and bazaars provided entertainment throughout the region. These activities helped to combat the idea of Communism as “sinister and foreign” among working-class people. It was in this environment that my grandmother Katherine Pyne became a Communist.

Hambledon State School

Hambledon State School was like many state schools throughout Queensland, yet unique in its own way. Established in 1887 as the Blackfellow’s Creek Provisional School, the original enrolment was 23 students.

This politically incorrectly named school was relocated to its present location on Mill Road in 1910 and renamed Hambledon State School. The name reflected the new location more than any new age of enlightenment regarding treatment of the region’s first people.

The school’s buildings were high set, which protected them from flooding. The underneath area had a cement base, which was a usable space for students during recess.

Next to the school was the Principal’s residence, offering affordable accommodation for the Principal and enhancing security for the school. The Principal providing passive surveillance after-hours. Such common-sense policies were common – prior to the curse of neo-liberalism, a disease of policy which infected the nation, with incomprehensible management lingo, asset sales and privatisation.

The Cane and Cultural Integration

When I started Grade 1 in 1972, the Principal was a Mr. Brady who looked very old to me. Brady only caned me once (so he can’t have been the Principal for very long). Many people in authority back then (and later) found me to be at best annoying and at worst, a thorn in their side.

State schools provided a community hub that brought together children from families throughout the township. So, public education more broadly was the driver of social integration. It brought together children from diverse cultural backgrounds, colour and class to learn and grow together.

Tom Murray

Grade 7 came in 1979, and my teacher was Mr. Tom Murray. Just above average height, Mr. Murray normally dressed in a shirt without a tie and what were described as ‘dress shorts’ and long socks pulled up to just below the knee. This was the attire of most Far North Queensland white-collar workers during this era.

Tom was the first teacher who I remember sincerely engaging in a two-way dialogue with students. I found these discussions interesting and they made me keen to learn. Despite my resistance to authority, I could tell when someone was sincere and wanted to make a difference.

The Murray family had a cane farm in Edmonton. As a teacher, Tom Murray encouraged students to develop their speaking skills and have some knowledge of the world around them. He also promoted civics and fostered community.

In 1988 at the age of 37, Tom married. Much to our surprise he married one of our class of 1979, Kathy Walter. Kathy would have been 20 by then. To be honest I am not sure if this caused any eyebrows to be raised, but I doubt it. After all, in a small country town like Edmonton, any teacher who ruled out relations with former students would risk celibacy.

State Education

My experience of state education was overwhelmingly positive. All my teachers, from old Miss. Hancock and Arthur O’Doherty to Anne Holden and Tom Murray were first-rate educators. My appreciation of Murray was shared by many in the community, and a park has been named in his honour. The park is located where the family’s old cane farm was in the middle of what is now the sprawling suburb of Mount Sheridan. It is located just off Hardy Road and there is space for children to run there, just as we did when it was cane land so many years ago.

Oliver Family

The state school system was my main contact with Aboriginal children and their families. The Oliver family was a well-known Edmonton family. Unlike most families, their ancestors had lived in the area not for a generation or two, but for thousands of years.

This proud aboriginal family lived on the corner of Graham Street and Mill Road. Alan Oliver was the family patriarch and worked for Council. I went to school with many of his children.

Alan’s wife May was a descendant of small people who lived in the rainforest on the Atherton Tablelands. May and Allan had 6 children and their daughter, named Mavis, was in my class at school (bottom-right below). As well as going to school with Mavis, I knew her brothers from school and rugby league. They were rugby league mad, as was their father who had a lifelong commitment to the Southern Suburbs Rugby League Club.

A White History for Us

One of the unfortunate aspects of the curriculum in the 1970s was the telling of a colonial history. That is to say, they taught us that Captain Cook “discovered Australia” in 1770. Text books told us the nation was founded with Captain Phillip’s settlement at Botany Bay in 1788.

We learned of explorers such as Ludwig Leichhardt, Edmund Kennedy and Burke and Wills, who discovered lands previously ‘unknown’. My classmates and I had no knowledge of the traditional owners. Consequently, we had no knowledge of their history or their stories of country. They taught about European identities. We heard of European voyages and accounts of the gold rush, including the Eureka stockade. I even remember learning of the barbaric behaviour towards the Chinese on the goldfields. They never mentioned Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

A Life Lesson from the Jones Boy

A small snowy haired boy by the name of Alan Jones transferred to Hambledon State School. I remember my mother saying he came from difficult home circumstances. Jones made an impact on me when I saw him being bullied by a couple of the larger kids.

The bullies pushed him over. Jones jumped to his feet. They pushed him over again. Jones jumped up again and started swinging punches like a wind turbine during a cyclone! He responded this way every time a larger child bullied him.

The diminutive Jones boy may not have done much damage, but the bullies knew they would cop at least a few swings from his energetic tirade. Realising it would take up an awful lot of their time and energy, they never bullied him again!

A Life Lesson

Whether in the schoolyard, politics or in management I have always hated bullies. I never forgot Jones’ response. It was a metaphor for how to engage with bullies. It really is better to die on your feet than live on your knees. I took this attitude with me later in life as I faced powerful enemies.

All Chapters

- Far North Queensland

- Growing up in Australia

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

- Queensland Political Culture

- Princess Alexandra Hospital Spinal Unit

- People with Disabilities

- Cairns Regional Council

- Conservative Cairns Council

- ALP Qld

- Abortion Law Reform

- Fighting Fossil Fuel

- Local Government Corruption

- Losing to Labor

- My Cairns Council Return

- Council Mayors Silencing Dissent

- Socialist Alliance and Fighting Fascism

- Jenny Pyne, Life and Pain

- Cairns Council Members Lurch Right

- Fightback and Farewell